Histories of shadows, architectural typologies for AlUla

Context

These proposals are taken from a more global study defining the AlUla master plan, commissioned by RCU (Royal Commission for AlUla) and AFALULA (Agence Française pour le développement d’AlUla). Winner of an international competition, this study carried out in 2020 by a group of designers and engineers, brought together by the landscape designers of the Ter Agency. In this group, Projectiles was in charge of the design of all the typologies and architectural guidelines.

The production presented herein is an extract of this work which synthesizes the architectural research. It is presented here according to two sets: agglomerated typologies, the category "villages" and scattered typologies, the category "Dialogues with the rock".

All of the projects cover a vast and linear territory, along the valley of the oasis and in the plain of Hegra.

The territory extends over 30km from north to south and 20km from east to west.

NATURE / CULTURE

A constant dialogue with nature is the cultural foundation of the civilisations of Alula.

Here, the landscape is enhanced by the dialogue between the architecture and the density of the mineral materials, the ochre of the sand, the yellow and red of the sandstone rocks, and the black of the volcanic plateau.

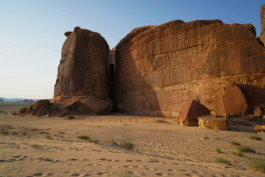

In the Hegra Plain, the mineral outcrops represent the iconic architectural figures of the Nabataeans of Alula. Polymorphic sandstone masses emerge like petrified mythological figures. They are the protectors of the Nabataean spirits.

Around the large valley that shelters the oasis, some cliff sides are pierced by Dadaite burial cavities.

The rock, which is omnipresent along the palm grove, forms crevices of different sizes and natures. Certain breaks in the rock are crossed by the annual rain flows coming from the basaltic plateau, while others, preserved from the torrents, offer formidable interior spaces conducive to peace and quiet, in the shade of the rocky slopes.

ALJADIDAH

Aljadidah bears witness to the architectural evolution through the centuries. It is a village where the different periods of construction stand side by side and juxtapose each other, a village that reveals the strata of time, identified by its agglomerated plurality creating a whole that is globally homogenous but diversified in detail.

We propose to enhance the village while keeping its character and limiting its expansion by dealing more specifically with its parameters: to the North, the sand, facing the village of Dadan; to the West, the vegetation, the transition with the oasis, opening the development towards the palm grove below; to the West, the rock, the relationship with the foot of the mountain; to the South, the earth, the face-to-face with the old earthen town. On each side, Aljadidah has a specific limit, an encounter with a material, a frontality adapted to what is juxtaposed to it. The spirit of intensification is inscribed in the heritage dimension of the sites by adopting the historical and mineral materiality, readapted to a discreetly contemporary architectural morphology.

Thus a play of solids and empty spaces is composed of scattered plots creating unexpected spatial dilations along the visitor's route, of transversal and traversing alleys, visually linking the oasis and the mountain, of tightly packed buildings sometimes separated by faults and pockets of vegetation (pocket gardens).

The height of the buildings varies from one to three levels, with a series of inhabited terraces for evenings, while during the day, the living space unfolds on the ground floor and in the interior gardens.

The materials present are mineral in all its forms, yellow and red sandstone, mud brick and rammed earth, sprayed earth plaster and plaster, and sometimes, if necessary, earth concrete.

Joinery, mostly in wood, is occasionally presented as small explosions of pastel colours. They borrow the popular mouldings made up of traditional geometric motifs.

New constructions, when they are made of stone, will vary in terms of mouldings and assembly methods. Vertical stratification will generally be ensured: the larger stones at the bottom forming a lower foundation strip to the building. The upper strata will be composed of smaller stones. Two successive buildings will not have the same façade layout. The variation of the façades, vertically and horizontally, ultimately forms a landscape of mineral patchwork.

The village buildings will be crowned by terraces occupied in the evenings, reinforcing the strong visual and landscape relationship between the village and the canopy of the oasis and the emergence of the rock masses.

Wadi

A wadi is the bed of a river that is dry most of the time. It comes alive and fills up during heavy rainfall. Once a year in AlUla, heavy rains fill the river bed and overflow into a large part of the oasis. The facilities we propose are spread out in the limits of the floodplain, on either side of the river bed, in the heart of the palm grove.

Historically, the inhabitants of the old town left their village during the summer to settle in the oasis, in the shade of the palm trees.

The summer dwellings consisted of earthen walls inside which the components of the house were scattered. The bedrooms and night-time communal areas were small mud constructions, while the kitchens and daytime communal living areas were set out in the open air, in the garden, in the shade of the palm trees.

The enclosures were organised around parallel primary arteries called ‘the Souk’, arranged along the wadi.

Thus, the palm grove is today inhabited by a vast network of earthen walls in a state of ruin, which we have invested as the base and the primary framework of a hybrid rurality, both mineral and vegetal.

Our proposals dialogue with the walls by declining different types of hangings and articulations to the historical enclosures.

Generally speaking, the oasis is made up of three plant strata. The upper stratum is defined by the tops of the palm trees, the middle stratum by fruit bushes, and the lower stratum by herbaceous plants. The habitats in the oasis benefit from a natural overhang generated by the canopy of the palm grove, creating a large area of shade and coolness. The thermal differential between the oasis and its outer limits generates a protective breeze. The earthen constructions are in the middle stratum, interacting with the shrubs and palm trunks.

The grid of the walls imposes a limit on the size of the habitats in the oasis. The reduced scale of the buildings also provides visual porosity in the depths of the palm grove.

Soil and palm wood are the main materials of the habitats in the oasis. Palm wood is traditionally used for the roof framework. A research laboratory is currently in place to find other uses for this very special wood, particularly for joinery.

DADAN

From the palm grove, a red mineral mass can be seen behind a layer of palm trees.

Coming from the South or the North, the visitor crosses a succession inside the palm grove, on either side of the road. The village suddenly reveals itself, like a clearing.

Unlike Aljadidah, Dadan is a homogeneous village, both in form and materiality.

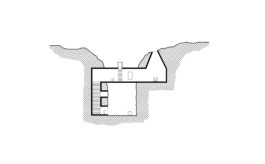

The shape of the village refers to the architecture of an archaeological excavation. Surrounded by the dense vegetation of the oasis on three sides, the village presents itself as a revelation, a discovery in the eyes of the visitors, as when one discovers an excavation.

Dadan is situated at the foot of the rocky mass of the same name. It is the emblem and spirit of the village. It is a single-material, built essentially with red sandstone, the dominant material of the immediate rocky mass.

The village is squat and close to the ground. Limited to two levels, the low height of the village allows a constant view of the surrounding rocky walls, especially the Dadaite tombs located on the other side of the oasis 40 metres above the ground.

Dadan is on the scale of a hamlet, whose architectural morphology borrows the poetic principles of an archaeological excavation. The general shape of the village evokes a footprint in the ground. The deep courtyards are one of the village's identity elements. These open spaces are private but collective meeting places and are true living spaces. These are precious spaces in their positioning and layout.

The lowering of the floors preserves the inner gardens below and increases the surface area of the shaded areas.

The coolness of the hollow spaces contributes fully to well-being.

From the streets, the village appears as a horizontal mass, limited in height. From the inside, the underground courtyards give height to the buildings, offering a surprise in the break in the vertical scale.The village is structured by a network of movements that sequences a series of squares, spatial dilations of different natures that can be discovered at each street corner. Two main arteries connect the oasis to the esplanade in front of the Kingdom Institute, forming a loop that runs lengthwise through the village. There is a secondary network of alleys, whose narrowness means that they are always in the shade.

Lastly, certain public spaces may be in hollows, like the inner courtyards, offering the possibility of enjoying maximum comfort and being away from the hustle and bustle while remaining within the network of public spaces. Courtyards allow you to isolate yourself from the urban noise level and to organise public events in complete tranquillity.

The treatment of the façades is a system based on the dimensions of the openings in the Danite tombs. The facade bays, arranged in different compositions, vary the proportion of the tombs at different scales with a slightly vertical proportion based on the measurement of H (height)=1.2 x W (width).

Generally speaking, the facade thicknesses form a second skin around the building, providing a buffer space for connecting levels and air circulation for better interior cooling. The double skin also makes it possible to manage what is opposite.

QARAQIR

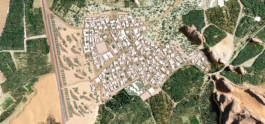

Qaraqir is a village inhabited by a local population deeply rooted in the region's agricultural activity and network. It has a family atmosphere. Here, the development consists in densifying the area while maintaining, as much as possible, the existing life and habitats.

Walking around Qaraqir, a soft and welcoming atmosphere is clearly perceptible. The landscape is majestic, dominated and crowned by the emergence of totemic rock masses whose bases are enshrouded by palm groves.

The walk between the rocks is very pleasant. Shadows and windy breezes are an ideal combination for the well-being of passers-by. This softness is to be preserved. The densification should accentuate the shadows and the effects of breezes.

Qaraqir has a quiet, intimate family atmosphere that must be preserved.

The public space must be hierarchical: very busy public spaces open to the village and more intimate public spaces. In order to vary the scales of spatial perception, from the most public to the most intimate, a reflection is made on the limits and porosities between major public space, collective space and private space.

One of the architectural components of the new development of the village is the set of walls, partitions and separating boundaries. They structure the space, invite people to walk, manage the private/public relationship, generate cover to maintain the thread of shade in the village and accompany the pedestrian on their journey.

Some walls can be freely traversed and more or less opened between two public spaces, thanks to porches, doors, porticoes and loopholes. If the plot is private, the wall thicknesses must integrate and manage visual porosities without disturbing the interior privacy.

The walls can also be partially inhabited by benches, diwans (alcoves with seating), fountains, plantations and above all, small shops such as micro-grocery shops or small refreshment bars, facing intimate public squares.

Around the water tower, the highest point in the village, the development plan provides for a major public area where the main public services are located. This area, from which the entire village can be seen, corresponds to the highest altimetry of the village.

Elsewhere, in a scattered manner, the general plan of Qaraqir South provides for the development of a series of plots whose scale corresponds to an urban breathing space for a micro-district. These are a series of collective spaces, where micro shops such as local grocery shops, accompanied by fountains, benches and trees are integrated into the thickness of the walls. These open, accessible areas are like pockets that one discovers by surprise in the middle of the density of the buildings.

In the image of the vertical organisation of an oasis in three plant strata, palm grove, fruit-bearing shrubs and herbaceous plants, the general landscape of Qaraqir is laid out according to a vertical stratification. The upper stratum corresponds to the rocky outcrops all around the village. Like ancestral figures, they seem to watch over the territory and give it its specificity. The high stratum is omnipresent. It is visible from all sides. It defines the background of all the visual framing of Qaraqir.

The middle stratum is inhabited by the tops of the palm groves, the occasional architectural emergence of the village's built structure and the inhabited roofs.

For this stratum, particular attention must be paid to the aesthetics of the numerous private water towers that emerge from the roofs. The plan-guide plans to propose a cladding for these micro-infrastructures.

The lower stratum is dominated by walls and their variations, public spaces and urban furniture.

The plan favours the development of inhabited roofs. In order to take full advantage of the landscape and the surrounding rock formations, the new constructions recommend roofs designed for use in the evening and sometimes to be able to sleep under the stars.

SILENT CITY

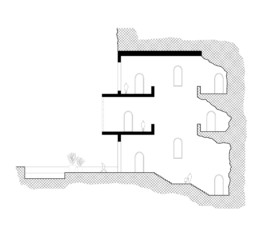

Silent City is invisible from afar.

When leaving the valley and the oasis, the traveller arriving in Hegra is unaware that there is a city nearby. Located in a vast desert plain, ‘Silent City’ is hollowed out of the ground and leaves only a tiny part of its scope visible. It is an autonomous density, hidden in the depths of the desert, inscribed like an imprint in the ground, in the middle of a large open area.

Silent City is connected to the world through its railway station and is the last stop, at the end of a world. The city is composed of a network of squares and inhabited layers that alternate in succession. As they walk through the city, the traveller is surprised by the calm that reigns there. A global silence prevails, regularly broken here by a conversation or a laugh, there by a lyrical flight coming plaintively from an oud. The serenity here bears witness to a timeless atmosphere. It could have been called ‘Stop City’, where everything stops. At the end of the line, one comes and then stays there, until the soul is appeased.

As the water table is not very far from the surface, the city dug into the ground benefits from its coolness. The succession of solids and empty spaces, the circulation galleries, the spatial constrictions and expansions, preserve the thread of shade and permanently create movements of air masses, conducive to overall refreshment. These same air currents are cooled further by gliding over a fountain or through a garden.

In this haven of peace, there are public baths, gardens, a museum, a restaurant, a market and a theatre. There are also several caravanserais for travellers who wish to spend a few days there.

At night, comfortably seated in the deckchairs on the roof terraces of the houses, the traveller can fully contemplate the immense constellation of stars and the density of the Milky Way. Here the night sky is pure, reminding us of our belonging to something much bigger than ourselves. We are in the midst of immensity.

Dialogue with rock

The morphology of the rocks and their layout offer a very rich set of spatial and climatic configurations. In particular, they generate shaded spaces that our architectural interventions seek to embrace. Here, being in the shade is a condition of life.

Our proposals define a series of specific architectures and extraordinary situations in constant dialogue and resonance with each of the rock configurations.

Inhabiting the folds and breaks of the rock, hiding in the thickness of the ground, settling at the top of a mineral emergence, living in the shade of the cliffs, penetrating the heart of the mountain.

Hegra South entrance

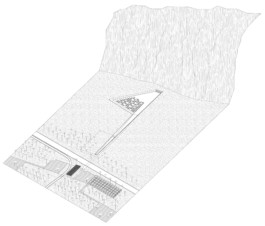

The Southern Entrance to Hegra is the last set to be built on the road to the site of the Nabataean remains. Positioned at the edge of one of the most impressive archaeological sites in the world, this very specific architecture must blend in perfectly with its natural environment. Here minerality dominates. Leaving the oasis with its palm groves behind, the site is marked by rock masses emerging from the horizontal and vast desert plain, like figures standing facing an infinite horizon.

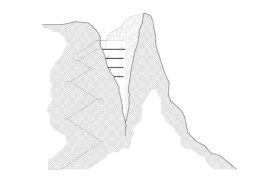

At the Hegra South entrance, the architecture is integrated in a large rock formation.

Lightly covered by sand dunes, this formation presents a more or less flat central zone perched 25meters from the ground and spreading in several direction with mounds of rock culminating at about 50 meters.

Arriving from the South-East, the train slips inside the rock and enters the middle of the fault made up of two large mineral walls marking the entrance to the station. At the West of the Southern slope, another fault of the same aspect indicates the second entrance.

This one is dedicated to shuttles and VIP cars and leads to a buried car park into the rock, from which visitors can access either to Hegra Museum with its Visitor Center or rent a buggy to go to visit the site directly. Inside the mountain, the station is an impressive volume which opens up to the sky at the end of the tram platforms: a skylight reveals the mineral thickness, frames the sky and invites visitors to progress into a rift. At the top of this fault offering a progressive ascension, the Visitor Center appears. Carved into the rock, it faces a buried courtyard fully open to the sky. A staircase extends the fault and continues the route towards another cavity which is built like a cloister forming an outdoor space of tranquility organized around a water body, to stay in the shade. The fault crosses thickness of the cloister, widens at the bottom and opens into a belvedere towards the landscape infinity. In the distance Hegra’s silhouette cuts through the horizon.

For the more adventurous, the route continues by a path climbing to the top of 2 rocky mounds where cavities are slightly dug and offer even more spectacular views towards the Hegra Site.

Project

Architectural typologies for the "Journey Through Time" masterplan

Location

AlUla, Saudi Arabia

Tender

Public

Surface

30km x 20km

Team

Agence Ter, Landscape designers, mandataries masterplan

Projectiles, architects

Setec Engineers (environment, energy, mobility, hydrology)

Franck Boutté Consultants (FBC), Sustainable development

Concepto, lighting designer

RCH, consultant in archeology and heritage

Horwath, consultant in tourism et hospitality

Aetc., consultant in cultural strategy and programming

Client

RCU (Royal Commission for AlUla

AFALULA (Agence Françasie pour le développement d'AlUla)

Phases

Lauréat du concours international > septembre 2019

Études du masterplan > décembre 2019 à décembre 2020

Share